Equine air flow in 3D

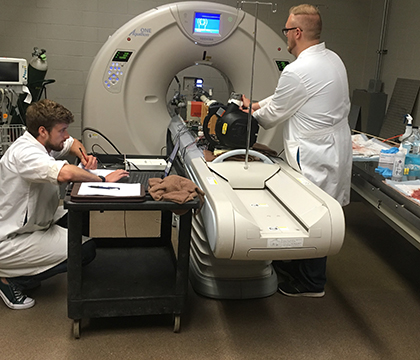

Research students Paul Thiessen (left) and Brendan Loewen take CT scans of an equine larynx while air is being blown through the imaging unit. Photo: Dr. Michelle Tucker.

A Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) research team is going back to the drawing board to find a better way of treating recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (RLN), also known as roaring, in horses.

Last year surgical specialists Drs. James Carmalt and David Wilson, along with surgical resident Dr. Michelle Tucker, were working on a new procedure that could replace a laryngoplasty — the current treatment method for RLN.

Surgeons can tie back the collapsed part of the horse’s larynx with a suture (laryngoplasty), or they can perform a partial arytenoidectomy (removing the arytenoid cartilage). But these procedures can cause complications: the laryngoplasty’s permanent suture can often become infected, and the arytenoidectomy can lead to feed contamination of the upper airway and pneumonia in some cases.

As an alternative, the WCVM researchers tested a corniculatectomy. As Tucker explains, the procedure is “less radical” than the arytenoidectomy because it only removes a small piece of the horse’s arytenoid cartilage.

“If you think about the larynx as a cartilage tube, [the arytenoidectomy] basically takes out one of the walls of the tube. So one of the concerns with that is that it destabilizes some of the airways,” says Tucker.

With the corniculatectomy, the researchers speculated that if they removed only the front part of the arytenoid and made a smoother surface, that would improve airflow. They tested this theory by using larynges from equine cadavers. Once the experimental procedure was done, the researchers put each larynx into a box attached to a vacuum to simulate the airflow of a galloping horse.

While the researchers found that the corniculatectomy didn’t improve the air flow in the equine larynges, they also noticed that the models using the arytenoidectomy performed just as poorly. Based on these results, the WCVM team members believe there’s a chance that the corniculatectomy could be effective in live patients.

“Basically, because it’s a dead structure, it collapses,” says Tucker. “So our suspicion now is, if we actually did it [a corniculatectomy] in a horse that recovered from surgery, it would work based on the fact that the arytenoidectomy worked. As well, our model can only account for so many factors.”

After receiving more funding from the Townsend Equine Health Research Fund this year, the WCVM team is collaborating with researchers from the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Engineering to develop a more precise computer model of a horse’s airway.

The engineers will create the computer model using the same physical model that was used during the previous study. The larynx model is placed in a CT (computed tomography) scanner while air is being blown through the imaging unit. Using the CT scans, the engineers can create the computer model with the proper dimensions and reactions to airflow. Next, the researchers can use the computer model to build a correlation between how the airway and the airflow interact.

“The engineers have a way that we can model based on the inflows and outflows … what the individual pressure is like at a lot of different points along the larynx. So hopefully, that will help us better understand what’s actually happening with the airflow in the horse’s throat,” says Tucker.

Before taking veterinary training at Texas A&M University, Tucker received her undergraduate degree in biosystems engineering and biology at the University of Kentucky. Tucker’s background has proved to be important, in more ways than one.

“It’s helped me a lot in being able to collaborate with the engineers,” says Tucker. “It has also contributed to the direction of the project because a lot of my ideas about doing the CTs and things like that came from some of the studies that they do over in engineering on other kinds of airflows.”

“We’re hoping that it’s going to change the way we approach surgery in some of these horses, especially given the fact that our first project kind of showed that individual horses are different,” says Tucker.

“What this may contribute to is a better understanding that one surgery doesn’t fit all.”

Harrison Brooks of Fort Qu’Appelle, Sask., is a third-year student at the University of Regina’s School of Journalism. Harrison is the summer research communications intern at the WCVM.

[…] at the WCVM, Tucker’s research focused on a condition known as recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (RLN) — also known as “roaring” in horses. The condition involves the degeneration of the recurrent laryngeal nerves, causing audible, […]